Guns versus smartphones

I’m just turning 75. My life has been formed, and is almost completed, throughout a breathtakingly brief and cataclysmic era in global history. In future accounts it may be referred to as ‘The Neoliberal Era’, ‘The Era Of American Hegemony’, ‘The Age Of Economic Globalization’, or perhaps, as the cataclysm intensifies toward its resolution, ‘Capitalism’s Final Crisis’. There will be a few references to something called ‘The American Empire’. It will appear as a flicker between the centuries, and one of the shortest lived empires that ever endured.

We are at the beginning of a 2nd American Revolution, one that is long due. Whatever the outcome, it will radically reshape the outcomes for global civilization. The age of the nation state is gradually going out of phase with the needs of the physical world. There will be times of breakdown and struggle. We must reintegrate with the workd. This will take some time and will never be at an end. I believe that in the next phase there will still be nations, and languages and cultural boundaries. The dimensions of power will be altered in structure and better managed, through education and the cultivation of respect. The flows of the twin rivers will be, at least until the next glacial scale disruption, in better harmony, as each distinctive part realizes its necessity to the whole.

Technology presents new perceptual models of the world much faster than anything we can control or even keep up with. We are continually confused. The time has arrived for us all to take a deep dive into questioning who we are and who we want to be, and what are the ultimate stakes. Complacency is deadly. We’d been so long buried in our own work, forgetting our reasons for working, or what makes up the whole mechanism of our survival.

We generally see and enterpret the word ’revolution’ to refer to specific cataclysmic changes in the procession of historical events. To understand what moves these events it’s necessary to go beyond specific dates and times and logistical patterns, and embrace the flowing evolutionary trends, ever constant, ever shifting, beneath the surface of what we see.

There are two constant revolutions/evolutions going on at any given historical moment. One is economic, and the other is cultural. They are woven together in close procession, at times in harmony, and at other times they appear to flow in opposing directions. The economic evolution is by nature conservative, its primary focus to preserve stability. Economics is a measure of the river of things, the movement of necessities and the produce of our desires.

Cultural evolution is something broader and more ephemeral, and yet central to our sense of well being. Something within us is driven by an impulse to break the rules, to advance, and to enter new territories. We are curious and inspired. Culture is the river of our perceptions. They are sometimes clear and accurate, and at other times only marginally connected to the world beneath the fog.

These twin streams never stop moving, never stop changing. They are inseparably linked, either energizing or obstructing each other, acting over and through us like the ancient gods in Greek tales about siblings and rivals.

It’s becoming abundantly and existentially clear to much of humanity that survival depends on a true understanding of the role we play as part of a bigger organism. Globalization is the political term for an economic transition. We go from centralized industrial production to widely distributed supply chains stretching across oceans and continents. At its essence, this is like the early evolution of the cell. A number of independent organisms come together as a cooperative community and eventually merge into a single complex organism. A process called symbioses.

Along with economic revolutions, cultural revolutions advance at an unprecedented rate, driven by the tides of information that flow through the system, reshaping at every instance our perception of the world.

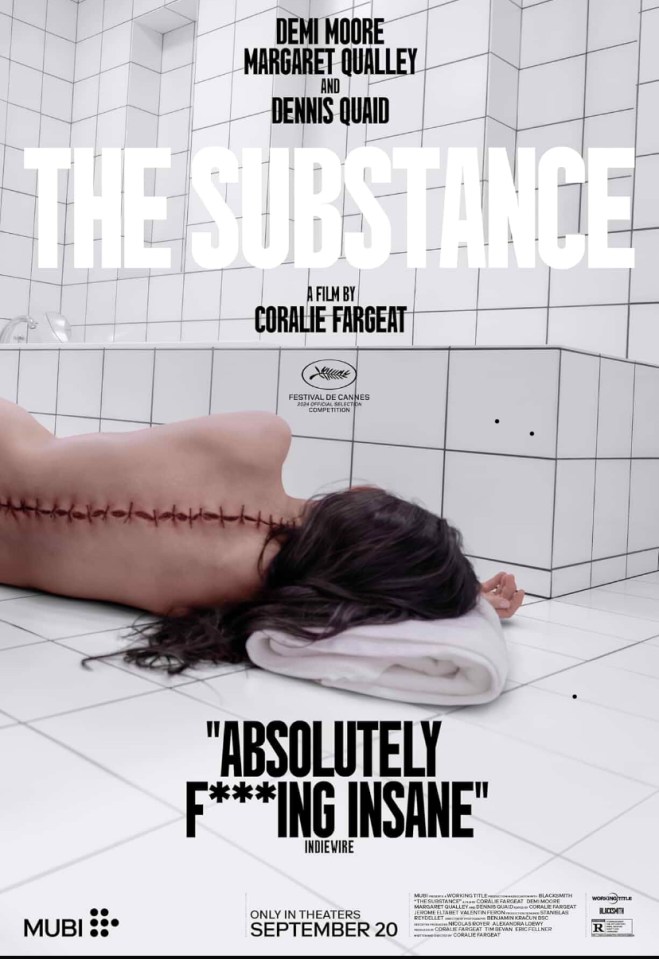

We are currently engaged in a third world war, which is a new kind of war, fought with numbers and ideas and conceptual systems playing across screens. The handheld weapon in this war is the smartphone in our pockets.

Things are moving very fast, worldwide…one event or action leads to others. People find out who their allies are. They’re encouraged to become more boldly resistant. A major university resists a government takeover. Prominent financial managers begin speaking out. Republican Town Meetings get rowdy. People, in general, are educating themselves. All of this builds toward an ultimate breakdown of life as usual.

Kilmer Abrego Garcia, like George Floyd before him, like Alfred Dreyfus long before all of this (see ‘Dreyfus Affair), is an unfortunate victim of history. On April 19th, demonstrations, even more enormous than on the 5th, will expand the focus beyond Musk and Trump to embrace and defend Garcia, and his young family, and ourselves, against the fascist brutality that landed him in a living hell.

Trump and company are waiting for an opportunity to gin up excuses to go after dissenters, with fierce repression, just as they did during the George Floyd era. Just like then, only more so, there’s an international reaction to their policies and cruelties, and they now feel cornered.

The American economy is now riding in the back of a cybertruck, under the control of the madman we gave the wheel, heading toward a Thelma and Louise denouement. I fully expect that we will go over that cliff, taking a good chunk of the world with us.

There is, at present, a very thin line standing between democracy and fascism in America, and the next few weeks will determine whether that line is holding. I’m talking about the Law, the Courts and the the Universities.

The 5th Estate, the Press and the Media are barely functional, not even willing, for the most part (except comedians), to call out fascism by its real name (they use the academic term, ‘authoritarianism’ – it’s elite and vague and sounds less threatening).

Social Media has taken up the slack of what remains of democracy and free speech, performing the role that pamphleteering did between the first American Revolution and the Civil War. I find myself no longer getting my news and analysis directly from newspapers or television, and the marketplace of ideas is boundless and international. This is a completely different realm of media, with a whole new set of rules, evolving constantly, that govern behavior and trust.

The vessel of our freedom is still encapsulated in words and institutions inspired and put into action more than two centuries past. If these barriers are breached, we will be in a new state of civil war. At that point another line of defense comes into play. There’s the police, the national guard, the military, led by educated commanders who’ve taken pledges to defend the Constitution and the law. These are forces composed of people from communities most affected by the actions of this administration. We will be in unknown territory.

We are in a Squeeze.

America will survive. The world will survive. The relationships between us all will be radically altered. We will have been through a deep process of self examination. Perhaps for the first time since the last World War, since FDR and long after, we will be forced into revisioning our entire political and economic culture.

My generation won’t be around to witness the conclusion of that process. But we will have been privileged to see its beginning, and to have learned much on the ride along the way.