“It’ll get easier. Someday it’ll all be done by machine. Information machines.” – Gravity’s Rainbow

I’m stranded in this Sargasso moment, awash above the blank pages in a sea of bewilderment, bordering too often on despair or at least demoralization, questioning who we are and what we are to do, placing words on screen or paper that appear too often useless. How can I meet the YouTube moment, while whole contraptions made out of outmoded words float like garish headlines against images appearing for short moments and then gone, while the world arranges itself around another passing crisis. What is it that endures against the nihilistic forces that stalk across the earth like a million metaphorical monsters, puncturing every dream and aspiration for no apparent purpose outside of the blind and momentary pleasure of watching things explode.

In my local community I’m like a ghost. What do I have to communicate besides brittle hope or the pain of loss? So much is lost to stupidity and greed. The question is, what remains?

I find some escape in the oceanic and ancient desert landscapes of this beautiful state as it flows past my car windows. I indulge in the exquisite paragraphs of my favorite writers, the best of them having been with me almost as long as I can remember.

I grew up in a post-war world of weekly air raid sirens and useless nuclear drills. I’d seen pictures of the bombs going off above Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and watched as ex Nazi Werner von Braun, on Disney, explained the nuclear reaction using ping pong balls and mousetraps. I endlessly fantasized about fallout shelters. My family drove past fields full of surplus tanks and obsolete aircraft on our way to church, all of this hardware useless in a war of total obliteration. I watched movies at Saturday matinees that featured mutant monsters wandering through the wreckage of civilizations. Most of my nightmares were of inescapable destruction.

The fathers of my generation gathered in VFW halls. They shared the fellowship of men and women who’d survived through a holocaust. They were often reluctant to reveal to their children any details of the horrors they’d encountered and survived. With fascination, we gleaned fragments and artifacts of memory from books and photographs. We watched television documentaries, roughly cut in black and white, narrated by Walter Cronkite or Edward R. Murrow, of battles and bombardments and ruined cities. There were the romanticized exploits in popular movies staring our favorite movie stars, portraying sacrifice, heroism and always victory. There were the morality plays of the TV westerns that dominated the evenings. As boys our favorite backyard fantasies featured plastic guns and makeshift arsenals. We retreated from history into our imaginations, and I guess it served as our defense against a backdrop of terror.

Amidst the doom and gloom and people taking themselves too seriously, there were other things to think about. Our childhoods, like every childhood, were filled with discovery and wonder. A fresh world of technological possibilities was opening all around us. Television itself was new. We launched ourselves into space, and the pace of ambition and invention was rapidly altering the landscape.

We thought about careers and success, and believed in times of growing tolerance and opportunities. Still, many of us found ourselves stranded in a marsh of questions and indecision. As the decades passed, we entered an extended interval of useless and dangerous conflict, of burning cities, assassination of our heroes, and a rising sense that civilization itself had an uncertain future. For those who stepped off the shores of safe and sound behavior, the plunge into unknown waters took a healthy sense of humor and a strong dose of aspiration, or at least enough momentum to move forward.

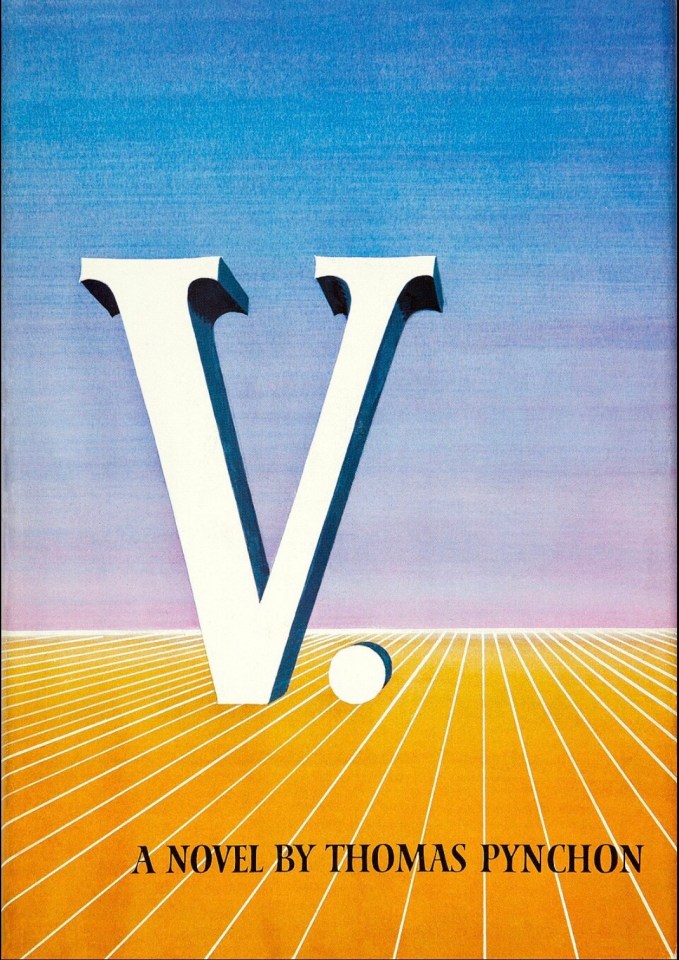

When I was 17 years old, I often wandered through the fiction racks in the downtown branch of the Carnegie library in my hometown, Cleveland. One day amid a display of the latest contemporary novels, I looked upon a thick and serious hardcover volume, with a single letter, V. , as its title. The letter stood monumental, upon a surrealistic plane of parallel lines converging toward a vanishing point, beneath an empty blue sky. In the foreground, in smaller letters below, the words proclaimed, A NOVEL BY THOMAS PYNCHON. Something about that image and title suited the world as I’d begun to see it, a mysterious and isolating landscape of endless searching and uncertainty. Like Pynchon’s characters in this, his first novel, my friends and I moved among bewildering scenarios with sensibilities that blended both hopefulness and paranoia. Like Pynchon’s Whole Sick Crew , we wandered amid the moral confusion that followed the chaos and tragedy of a World War. Underneath it all there lingered the frightening suspicion that everything that might have made sense to our parents was on the edge of coming apart.

Thomas Pynchon writes in the words of a prophet, a comedian, a poet of times of transition, when one world collapses into another, and people find themselves somewhat lost, seeking some kind of anchor in the tempest. His novels are mysteries. They take us, along with their sketchily drawn protagonists, to witness worlds both bizarre and familiar, packed with lush detail, profoundly beautiful and monstrously grotesque, full of both darkness and hilarity. His characters, as they search for patterns that might reveal some sense of ultimate purpose, skirt the edges of discovery, driven forward by circumstance, picking up messages and signs that hopefully provide clues, or at least an indication of direction. Each of his novels takes us through the beauty and violence of landscapes in a different period of history. We hang out with Benny Profane and Herbert Stencil in the 1950’s, with Oedipa Maas through the Los Angeles real estate boom of the 60’s, Tyrone Slothrop in the zones of Europe at the end of World War Two, Zoyd Wheeler navigating Reagan’s War On Drugs, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon measuring the border that would split America against itself, and the world between spirit and reason in the 1700’s, the Chums Of Chance exploring the realms of fantasy and possibility at the 1893 Columbian Exhibition, flying ever forward toward the ‘War To End All Wars’. Thousands of characters make their appearances, however brief. The style is said to be encyclopedic, and it is, dealing not merely with characters and events, but with the sensibilities of every moment, where the mythical blends into the factual, the imaginative informs the real. He surveys the fleeting joys, horrors, and absurdities of all times. We shift among as many points of view as there are situations, and at times his people might even break into songs and poetry, even limericks, to change or illuminate the mood. Pynchon’s writing challenges and even breaks many of the conventions of prose, as if he’s daring us to trade in our box of expectations for a new sense of freedom.

There are dozens of essays and books written about and/or inspired by Pynchon, and as many interpretations of his work. I can offer my own, although it’s continually under revision. Like a trickster he challenges us to see through the patterns of history into worlds always in flux, driven as much by imagination as intent, old orders always collapsing while new ones arrive, never quite reaching a conclusion. We see humanity in a constant struggle between opposing urges of freedom and control, and beneath all the hopes, the curiosity and the paranoia, finding no final answer beyond the absolute mystery of beginnings and endings, and everything inbetween.

Pynchon is one of the most influential writers of his generation. He certainly influenced me. Through the years every one of his reviewers and readers has attempted to plumb the mysteries and meanings that thread through his voluminous work. The worlds he creates are both beautiful and monstrous, and each is a maze littered with both absurdity and wisdom. Pynchon himself is a cipher, almost never photographed and he’s never sat for an interview. As far as I know he’s never offered explanations outside of his work, thus leaving any conclusions fully to the reader.

My personal enjoyment is in his magnificent sentences, lush and long, often the length of a whole page or paragraph, exquisite and wanting to roll off the tongue, more like poetry than prose, or maybe something in between. They are filled with the beautiful, the mundane, the grotesque, the enigmatic and the profound, and the sheer adventure in reading them has gotten me through some very difficult times.

Here’s an example, from Against The Day.

Yashmeen’s white tall figure, parasol over her shoulder, already a ghost in full sunlight, went fading into the crowds flowing in and out through the trees between the quay and the Piazza Grande…

…Plum and pomegranate trees were coming into flower, incandescently white and red. The last patches of snow had nearly departed the indigo shadows of south-facing stone walls, and sows and piglets ran oinking cheerfully in the muddy streets. Newly parental swallows were assaulting humans they considered intrusive. At a cafe off Katunska Ulica near the marketplace, Cyprian, sitting across a table from the cooing couple (whose chief distinction from pigeons, he reflected, must be that pigeons were more direct about shitting on one), at great personal effort keeping his expression free of annoyance, was visited by a Cosmic Revelation, dropping from the sky like pigeon shit, namely that Love, which people like Bevis and Jacintha no doubt imagined as a single Force at large in the world, was in fact more like the 333,000 or however many different forms of Brahma worshipped by the Hindus—the summation, at any given moment, of all the varied subgods of love that mortal millions of lovers, in limitless dance, happened to be devoting themselves to. Yes, and ever so much luck to them all.